(CNN) — The obituary for Marianne Theresa Johnson-Reddick that appeared in the Reno Gazette-Journal on September 10 started in typical fashion: She was born on January 4, 1935 and died on August 30, 2013. But the announcement, written by two of her adult children, quickly took a grim turn.

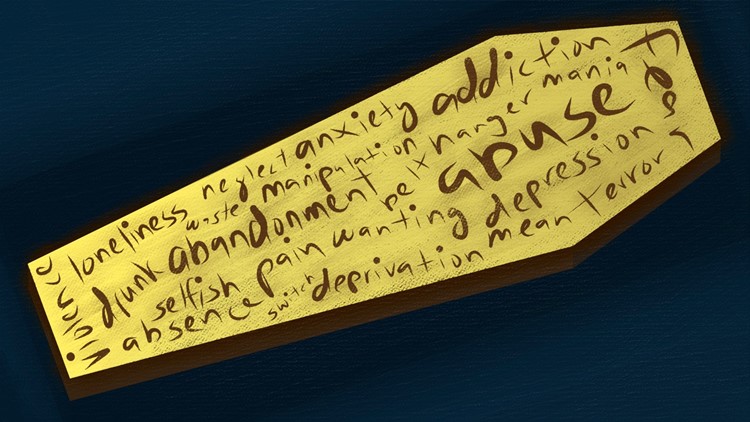

While most death notices include a short, factual and sometimes cheery biography of the deceased, this one included a laundry list of Johnson-Reddick’s alleged parental failings and character flaws.

“She is survived by her 6 of 8 children whom she spent her lifetime torturing in every way possible,” the obituary read. “While she neglected and abused her small children, she refused to allow anyone else to care or show compassion towards them.”

The obit was submitted via the paper’s self-service online portal, according to publisher John Maher, and it quickly went viral. Patrick and Katherine Reddick co-wrote the scathing remembrance, and Patrick has gone on to tell publications he sang the Wizard of Oz’s “Ding-Dong! The Witch is Dead” when he learned of his mother’s passing.

The cemetery isn’t always an easy place to bury the hatchet, especially when survivors remember the deceased in an adversarial light. What do “My condolences” or “I’m sorry for your loss” mean to a person who is thinking “Good riddance”? And how do resentful survivors avoid speaking ill of the dead?

Grief experts say people affected by the death of a less-than-loved one often have much more unfinished emotional business, and that business starts with forgiveness of a sort.

The Reddick siblings claimed in the obituary that their motive was “to stimulate a national movement” against child abuse in the United States. “Her surviving children will now live the rest of their lives with the peace of knowing their nightmare finally has some form of closure,” they wrote.

Russell Friedman, executive director of the Grief Recovery Institute, said even the death of a toxic person can’t bring the closure the Reddick siblings mention when grief is unresolved.

“Grieving people tend to create larger-than-life pictures in which they enshrine or bedevil the person who died,” he said.

Friedman says rehashing tough memories in an obituary like Johnson-Reddick’s keeps survivors mired in pain and grief.

“When they’re telling the story of their pain, there’s no recovery. Where is the completion,” he asked. “They’re just confirming the pain that’s built in; the pain becomes their identity. The pain is not freedom; it’s jail.”

Some survivors of heinous abuse agree that holding onto hatred for the dead and publicly shaming them will not close the book on a lifetime of hurt.

Becky Blanton knows what unresolved grief feels like. Her essay detailing alleged physical and sexual abuse at the hands of her father, titled “The Monster,” appeared in the late journalist Tim Russert’s final book “Wisdom of Our Fathers” and outlines how she came to terms with his abuse while he was on his death bed.

Blanton said the only way to overcome pain caused by an instrumental figure in one’s life is to forgive, but the definition of that word is often misunderstood.

Both Blanton and Friedman said forgiveness is about relieving oneself of resentment.

“Forgiveness isn’t about saying, ‘It’s OK,’ or that you ‘accept’ or ‘approve’ what happened,” Blanton said. “Forgiveness is the acknowledgment that what happened, happened, and that you are now ready to set down the baggage, the pain and the fear.”

“There simply is no other way,” Friedman agreed.

Blanton finds that when a person forgives they no longer take action based on feelings of revenge, anger or fear, but instead make decisions based on their own character.

“If I consider myself a good person, a generous person, but then act meanly or selfishly because someone has treated me that way, then I allow their actions to determine my character and my actions,” Blanton said.

Friedman said that without taking the proper steps to grieve and let go, pain can become part of one’s identity.

“(Retribution) does no virtue for you. It will create the illusion that you’ve done something valuable for yourself,” Friedman said.

Resolving that pain comes down to a key phrase: “I remember the time that you did this, and I’m not going to let the memory of that event hurt me anymore.”

There are ways to describe a person of dubious character after death without blasting them in an obit, according to Andrew Meacham, the chief epilogue writer for the Tampa Bay Times.

“Just as people aren’t saintly, they aren’t completely villainous,” he said.

“You don’t have to make somebody out to be a villain, just tell the facts and people can read between the lines,” Meacham explained.

Just as he says he avoids writing biographies in which that person “never met a stranger,” had a “smile that lit up a room” and the rest of those hanky clichés that come out when somebody dies, he also avoids the opposite.

“Had I written (the Johnson-Reddick obit) as a news story, I would want to talk to somebody who knew their mom,” he said. “Not necessarily to sanitize it, but she was a human being after all.”

Meanwhile, trying to console a person who has experienced a loss is tricky — especially if the relationship was contentious. Above all, Friedman recommends being mindful of the words you use.

“I’m sorry for your loss” doesn’t work, Friedman said. “‘I’m sorry’ is a dangerous line if you didn’t know the person who died.”

Friedman suggests instead using open-ended phrases like: “I don’t even know what to say. I can’t imagine what this has been like for you.” Turn the statement into more of a question, giving the person an opening to tell you the truth if they feel up to it.

Blanton agrees.

“‘I’m sorry for your loss,’ doesn’t cut it when a person is a monster,” Blanton said. “Having someone say, ‘I’m so sorry for what he did to you. I wish someone had been there for you’ does wonders.”

Blanton sees where the Reddicks were coming from. They are trying to be heard because they might not have been able to express anger as children (or were too scared to), she said, and they’re doing the best they can with the tools they have.

Her response: “We hear you.”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2013 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.