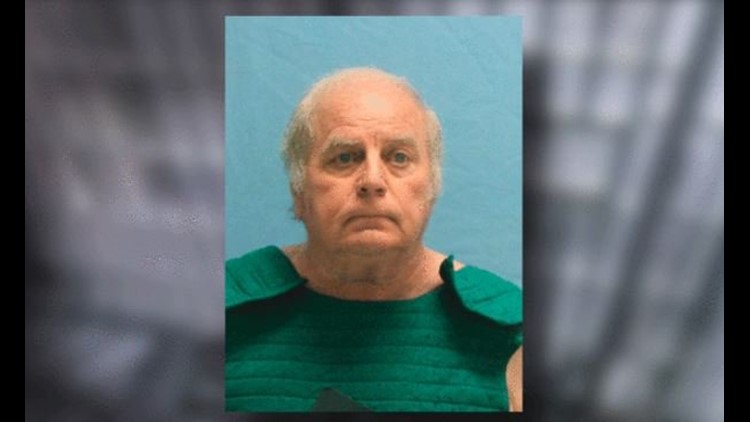

LITTLE ROCK, Ark. (CBS News) — A federal judge sentenced a former Arkansas judge Wednesday to five years in prison – a stiffer punishment than prosecutors recommended – after he admitted giving young male defendants lighter sentences in return for personal benefits that included sexual favors.

Joseph Boeckmann’s lawyer had wanted home detention for the 72-year-old, and prosecutors said he should go to prison for just over three years. After hearing from two of the ex-judge’s victims, U.S. District Judge Kristine Baker said she had no choice but to impose an even longer sentence.

“He acted corruptly while serving as a judge. When his back was against the wall, he obstructed justice,” Baker said. “That sets his crime apart.”

Prosecutors said Boeckmann’s pattern of misbehavior dated at least to the 1990s, when he was investigated while a part-time deputy Cross County prosecutor. Federal prosecutors decided against charging him after he agreed to give up his post in 1998.

Richard Milliman of Memphis, Tennessee, became one of Boeckmann’s victims after being stopped for driving five miles per hour over the speed limit four years ago, then forgetting his trial date. The judge summoned Milliman to his house and took photos of him from behind as he picked up cans under the guise of performing community service, then shot photos of some of Milliman’s tattoos.

Milliman, then 23, said he refused to pose David-like, even though he was offered $300 to mimic the Michelangelo work.

“I’ve never felt more betrayed by the justice system,” Milliman told Baker, imploring her to impose a longer sentence than the 30- to 37-month term called for in federal sentencing guidelines. “How can a mere 37 months be a means to pay back society?”

Boeckmann sat with his lips pursed at the defense table.

Prosecutors said the number of victims could be in the dozens or hundreds. Typically, the former district court judge dismissed traffic citations and misdemeanors in exchange for “community service” that, in some cases, required some young men to submit to photographs in compromising positions, but in others, required sexually-related conduct.

Kyle Butler said he was also forced to pose for photos and was threatened with his life if he didn’t recant information he had given to state investigators.

In a letter written before Wednesday’s hearing – a portion of which was read to the judge – Hunter said that after Boeckmann had helped him following a traffic accident, the judge required him to routinely clean up a laptop computer that had been slowed down by a cache of X-rated pictures and videos.

“I had to do as he said. He held all the keys to my freedom,” Butler said.

Boeckmann’s lawyer did not want the judge to consider the 1990s investigations, saying the ex-judge’s memory was such that he couldn’t refute any allegations. Baker said she found the misconduct pertinent, given that FBI agents were told then by Boeckmann’s secretary about her finding nude photographs of young men in his office.

The ex-judge spoke to Baker briefly and in a barely audible voice said he had tried to convince himself that he wasn’t doing anything wrong. He later added, “I’ve had time to reflect.”

Boeckmann had faced up to 260 years behind bars if convicted of all charges in the 21-count indictment. He pleaded guilty last year to mail fraud and witness tampering.

When Boeckmann left his deputy prosecutor’s job in the 1990s, he was able to keep his law license – making him eligible to run for the bench. As it investigated Boeckmann’s behavior more recently, and subsequently negotiated his resignation, the head of the Arkansas Judicial Discipline and Disability Commission, David Sachar, demanded that the judge agree to never seek any elective office again.

Milliman said it was shame that Boeckmann had another opportunity to prey on more young men who would find it difficult to step forward.

“How are you supposed to talk about another man violating you?” said Milliman, who drew a line at how much Boeckmann could photograph at their only non-courtroom encounter. “Why wasn’t it stopped long before now?”

Milliman and Butler were identified by aliases in court documents but both said Wednesday they wanted to speak openly about the judge’s crimes.