(CNN) — Although he’s older than the Giza pyramids and Stonehenge, the 5,300-year-old mummy of Otzi the Tyrolean Iceman continues to teach us things.

The latest study of the weapons he was found with, published in the journal PLOS ONE on Wednesday, reveals that Otzi was right-handed and had recently resharpened and reshaped some of his tools before his death. They were able to determine this by using high-powered microscopes to analyze the traces of wear on his tools.

The upper half of the Iceman’s body was accidentally discovered by a vacationing German couple hiking in the North Italian Alps in 1991. Otzi was found with a dagger, borer, flake, antler retoucher and arrowheads. But some of the stone was collected from different areas in Italy’s Trentino region, which would have been about 43.5 miles from where he was thought to live.

“Through analyzing the Iceman’s toolkit from different viewpoints and reconstructing the entire life cycle of each instrument, we were able to gain insights into Otzi’s cultural background, his individual history and his last hectic days,” Ursula Wierer, study author and archaeologist, wrote in an email.

“The Iceman travelled with a compact lithic toolkit formed by few worn out, repeatedly resharpened tools, mostly used for cutting plants. Ötzi was a righthander and had a quite good skill in pressure flaking by using his own functional retoucher.”

And when compared with artifacts recovered from the Copper Age, when the Iceman lived, it appears that his tools were stylistically influenced by other Alpine cultures. Clearly, the 46-year-old Iceman, who lived in the South Tyrol region of Northern Italy between 3100 and 3370 BC, survived by staying on the move.

That is, until he was violently killed.

These new findings add to the wealth of knowledge we’ve gained about this mysterious figure. Here’s what else we know about the Iceman and how he was killed.

Cold case

Otzi became a glacier mummy through a unique set of circumstances. He was crossing the Tisenjoch pass in the Val Senales valley of South Tyrol when he was shot in the back with an arrow by a Southern Alpine archer and became naturally preserved in the ice. Otzi, his clothing and his tools were remarkably well-preserved.

The arrowhead is still embedded in his left shoulder and wasn’t found until 2001. He would have bled out and died shortly after because it pierced a vital artery. There is also a wound on the back of his head, but that may have occurred when he fell after being struck by the arrow.

A cut on his right hand, indicating hand-to-hand combat, never had a chance to heal before he died. This means that conflict happened before he was shot, perhaps hours or days before, and may have led to the second conflict that killed him.

The injury to his right hand would have made it difficult for Otzi to prepare his weapons in case of another attack. This is most likely why the bow and arrows found with him were unfinished: to replace ones that were lost or damaged in the previous conflict.

But the motive for his killing is unclear, because he was found with a very valuable copper ax. It is the only one of its kind ever discovered and could have functioned as a weapon and tool, as well as a status symbol. During the Copper Age, copper axes were owned by men of rank and buried with them. Copper was the first metal used to make weapons and tools.

During the Copper Age, metal was extracted and smelted, creating new trades and professions. This increased long-distance trade, boosted exchanges among cultures and led to the rise of new social groups.

Since 1998, Otzi and his artifacts have been on display at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy. He was nicknamed Otzi because he was found in the Otztal Alps of South Tyrol.

His clothing, made from leather, hide, braided grass and animal sinews, provides a unique window into the past because other clothing from that time has never been recovered. His hide coat, leggings, loincloth, belt, fur shoes and bearskin cap would have kept him warm in the cold, wet climate.

He also carried a type of wooden backpack, containers made of birch bark rather than breakable pottery, the ax, an unfinished longbow, a quiver of arrows in progress, a flint dagger, a retoucher to sharpen blades, birch fungus to start fires or use as a therapeutic, and a stone disc to attach things to his belt.

One of the most-studied mummies

Otzi was briefly “thawed out” in 2010 so researchers could take tissue samples, and remarkably, he was so well-preserved that red blood cells were recovered. His nuclear genome was isolated in 2011. This revealed not only his blood type but his ancestry, appearance, medical conditions and predispositions to disease.

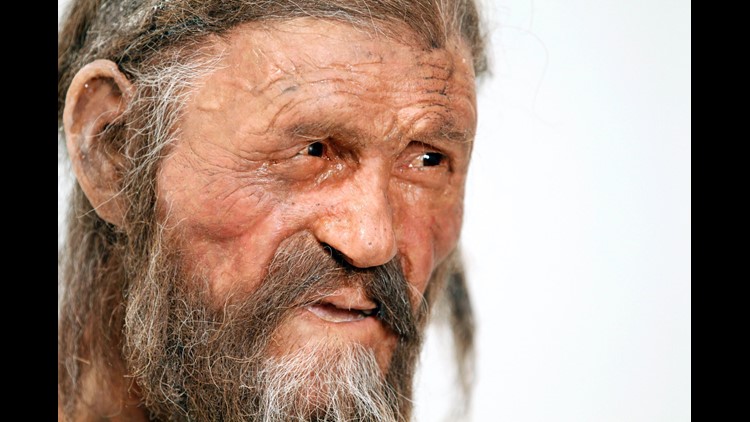

A reconstruction of Otzi, based on forensics and 3D modeling, showcases what he may have looked like in life.

He stood at 5 feet 2 inches tall and had a slightly muscular build of 110 pounds, a narrow and pointed face, tanned skin, brown eyes, long dark hair and a shaggy beard. His blood type was O-positive, and he was lactose-intolerant.

Otzi had a high risk of cardiovascular disease and traces of Borrelia, tick-borne bacteria that cause Lyme disease, in his genome. Bacteria in his stomach could have led to stomach ulcers. He had intestinal whipworms.

His age was considered old at the time, and he probably had arthritis. There are tattoos all over his body, specifically in places that might be considered therapeutic for someone with arthritis — especially because they couldn’t be seen if he was clothed.

On his father’s side, Otzi had common ancestors with those who lived in Sardinia and Corsica and migrated to Europe from the east. His mother’s side could be traced to a population from the central Alps that doesn’t exist anymore.

His last meal, most likely an hour before his death, included grain and ibex and deer meat.

But many questions remain. What was his occupation? Why was he nomadic during a time of settlements? Why was he killed? The ongoing investigation into Otzi may uncover those answers in the future.